On a sun-filled and breezy afternoon in May, Sawsan Bou Khaled sits quietly in a corner of a Beirut café gazing at a photo she took of Kinkaku-Ji, Temple of the Golden Pavilion, in Kyoto. The temple is elaborate, covered in gold and adorned with gilded leaves; it was designed not only to alleviate and dispel negative thoughts and feelings about death but also to create a backdrop of visual excess. Sawsan has recently returned from Japan, where she took part in the World Theatre Festival in Shizuoka with her latest theatre performance entitled ‘Alice’, and her artistic world appears closely tied to the spirit of Kinkaku-Ji. Just as the temple’s shimmering excess is deployed to promote an acceptance of death, so Sawsan embraces a similar philosophy in both her directing and performance where visual display is harnessed to present death on stage. They are worlds and forms apart but a common thread runs between them providing the basis for new narratives.

However, the story here is different focusing on the views of the young author, director and performer in relation to a situation of limitations: that of borders across the discipline of art. It is important to note that Sawsan has performed in a number of countries including Algeria, Belgium, Egypt, France, Japan, Jordan, Luxembourg, Sweden, Syria, Tunisia, and her native Lebanon. Having crossed borders to present her work and collaborate with other (performance) artists, the main border that Sawsan Bou Khaled faces today remains – quite literally – close to her heart.

Personal Borders

A.Z: What is the border that you feel is most present within your work, and how does it create restrictions or grant you access to new territories?

S.BK: When I think about how a border can impact upon me artistically, the first border that comes to mind is that of my own body. I think most performance artists have a powerful relationship with their body - one that they try to break or strengthen. Personally, the first border to cross is my own and my work focuses on that dichotomy of sorts. What lies beyond my body? Just as one might be faced with a physical border, exploiting what lies within my being and transforming, distorting and reshaping it after experimenting with its limitations is a difficult task. At the same time it brings me much needed security. Once on stage, you’ll often hear performers say that they are naked – even if not literally. When I’m performing in public after weeks or months in private, it is my body that unconsciously takes control and not my mind. There lies a parallel time and space where I am conscious about what I am doing and saying while surrendering to my physical self. On stage, the border of the body is opened and access is through communication. But once my body fails me, I know I’ll no longer be able to perform as an artist.

A.Z: How so?

S.BK: Well my body as a border has a continuously evolving form and space. However, if this process of constant experimentation should end, no longer enabling me to engage in an honest and engaging dialogue, then I believe that I would have nothing more to share.

A.Z: This border you are speaking of; how does it shape an audience’s perception of your performance?

S.BK: The fact that my work draws on all those personal experiences that have formed the person I am today enables me to create a performance that is not just a one-dimensional transmission of a particular message or image. I work hard on the visual aspect of any artistic creation to create an impact on the audience and I draw heavily on the use of personal symbols that represent moments of my childhood and life in general. The physical border here is the stage, or the site in which the performance takes place, it delimits the audience’s physical involvement, at the same time as providing a space for them to observe and communicate with what they see and hear.

I have no interest in inviting an audience to feel compassionate towards me, or my work. What excites me about performance art is the space in between that you can develop and manipulate to create abstract ties with the public. I want the audience to reflect upon their own monsters and personal narratives as opposed to putting themselves in my shoes to feel emotion. The border that is my body – the first border I face – is open on stage and used as a tool to encourage myself and others to discover a new dimension. The border I draw on stage is permeable and is crossed when the audience and I enter into communication.

A.Z: What are your own monsters?

S.BK: I have many, and they all play into the central theme of death that is omnipresent in my work and which I believe lies at the core of theatre more generally. My work is not focused on a situation that is relevant in time, and many of my fears and desires – if not all – form an integral part of my statement as a performer. Another central theme, or monster, is injustice. I am looking for a fairer, more just world.

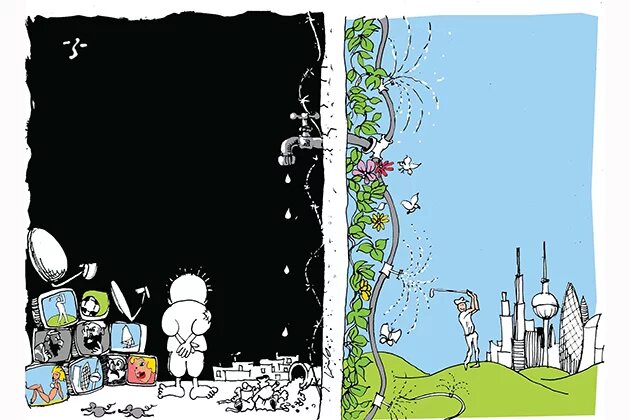

I live in a region plagued with injustices and there is no way of ignoring that artistically. I feel a certain responsibility for these injustices and it is important that I position myself as someone who recognizes how historical and contemporary power-struggles have created the current situation. The centres of power are spread unevenly globally, and people from different cities, nations, and continents don’t feel involved with or culpable for what happens to their neighbours. That – to me – is a supreme injustice.

Artistic Limitations and Culture Vultures

Artistic limitations may be dangerous. These fragile lines of separation presume that what occurs here is irrespective of what happens there. The most intangible of borders are also the sites of interaction and dialogue within the global art scene. A place where artists and their works travel to be exhibited within certain frameworks and an understanding of what art is. As Sawsan and I deliberated over these specific limitations our conversation moved into a discussion around the power of culture-specific borders and crossings.

A.Z: Could you tell me a little more about the borders of nations in relationship to your work as a female artist from Lebanon?

S.BK: I don’t refer to myself as a female artist from Lebanon. I believe that labelling yourself in terms of sex and geography provides others with a tool that they may use to form a perception of your work, an approach that I am not comfortable with. I want others to engage with my work through their own understanding of it, of course, but also through the hand that I extend to guide their way. Ultimately, it is up to each member of the audience to decide whether or not they wish to accept the invitation. I also believe that such labels are used to reinforce the binary relationship of powerful versus weak.

A.Z: How so?

S.BK: There are many instances. For example, the West is more inclined to view itself, as it always has historically, as the benchmark for cultural superiority. Colonization, and the remnants of its legacy, puts us in an awkward position as artists. The times my work has travelled to Europe to be exhibited have been enriching, albeit disturbing at times. I think that the borders Europe has set in place aren’t so much physical as cultural, and people need to traverse a less customary path to form a clearer understanding of what the world is like on the other side. Artistically-speaking, I believe this would really enrich people’s perception of the region in terms of reshaping the viewing-angle with which they measure artistic creations. I have no interest in playing the victim in the context of exoticized war and violence, and too often that is the case when work that happens to be from the Arab World is exhibited. The level of critique usually applied to artists from a more privileged world doesn’t appear to be employed when reviewing the work of less fortunate artists.

At the same time, the art world is like a market enclosed by pretty fencing. There, curators, programmers, and institutions invite artists to sell their work. Some look attractive, others a little less so. Some are relevant to what is currently in vogue and others are irrelevant to what is in vogue from the outset. Some markets are also better than others, or at least are believed to be, and having your ‘produce’ presented there is a long process. I just don’t have much that I’d like to sell.

A.Z: Having your work shown at prestigious festivals may very well enable it to travel further and reach other audiences. Are you suggesting that the border to cross in order to present your work in the West is not a border worth treading?

S.BK: I’d love nothing more than to establish lines of communication with extended audiences, to have my work resonate with diverse crowds and to see the ways in which different people react and respond. Disrupting expected responses and confirming others… At the same time, I try to remember the reasons my work travels abroad. In my opinion, my work should only go abroad if it might actually resonate with an audience or provide a new territory for exploration rather than crossing boundaries simply because I’m a performer of a certain calibre, ethnicity or region. Furthermore, there’s a limitation imposed on artists from the region, they either fall into the category of ‘victim’ or ‘ally’. People on either side seem to refuse the idea that our fates are all interconnected despite the terrains and oceans that set us apart. It is important that, in cases where this happens, the public is aware of their responsibility. I want to promote the idea that we are all a part of the world’s glory and its demise – and I want the audience to think about the part they have to play within this.

I’m also aware that if I become a successful performer abroad, the chances of me touring the region could and would grow exponentially, and that frightens me.

Regional Deception

A.Z: And within the region itself: do you think it is possible to grow and share with artists and groups from other nations? What are the obstacles?

S.BK: The ministries of culture in our region have weak cultural policies and don’t equitably finance artists and artist spaces. Instead, we have institutions and associations that work more seriously to distribute funds and provide grants. Many of these entities happen to be European and American, and a number of others receive funding from organizations in the West. Thanks to these organizations, many artists are able to create and flourish. I happen to be working more on the edge here, searching for different ways to evolve and connect. It’s just unfortunate that although the opportunities are there, many artists feel they need to reshape their designs in order to fit the application brief, eventually resulting in works and subjects that have been adapted to cater for what is desired.

Making connections on one’s own is rather difficult, and a large number of these collaborations are low-key (that is not to say that they are in any way less important!). I think that one of the main obstacles in the region is that of corruption and the situation we are in as nations and societies is a direct result of dire policies and cultural hegemony from abroad. It is also striking to see how we still hold on to our colonial history in a desire for better times. In many ways we also seem to use this to evaluate ourselves artistically and I think that’s really quite tragic.

A.Z: Any hope that this will change? Will the cultural borders of the Arab World open up and organically branch out?

S.BK: Although it is slow, I do believe that it is already happening. At one point, with the seemingly blossoming Arab Spring, we began building hope and bridges with one another across the region. We had the intention and the desire to connect and create a more prosperous region thereby reaffirming our multiple and rich identities. There’s no need to review where we are now, as despite the progress that has been made, there have also been many setbacks to overcome. But there is always hope!

Hours have passed and the sun begins to set, projecting rays of gold on the off-white walls of the apartment building facing the café. A friend has arrived and asked to join us on the table, to which we agree without hesitation. ‘If I say border, what’s the first thing that comes to mind?’ – I ask, to which he replies ‘Borderless!’ Ah, to live in a world that is free of borders…